Niam n'goura

Between filiation and dissidence towards a Senegalese art

SOLY CISSÉ, ALIOU DIACK, VIYÉ DIBA, THÉODORE DIOUF

11 - 20 SEPTEMBRE 2024

SALON AM MORITZPLATZ, BERLIN, ALLEMAGNE

Curated by Jeewi Lee et Océane Harati

RETOUR

PRÉSENTATION

Par Charlotte Lidon

‘The Festival will be an illustration of negritude [...] a positive contribution to the building of universal civilisation. In other words, we will have ceased, for ever, to be consumers, to be, at last! ourselves, producers of civilisation’ (2) - Senghor 1963

The exhibition Niam n'goura (1), between filiation and dissidence towards a Senegalese art is a rare opportunity to present four generations of artists from prestigious Senegalese art schools to the German public, the first of which was founded just after independence in 1960 by President Léopold Sédar Senghor. (3)

Théodore Diouf (born in 1949), Viyé Diba (born in 1954), Soly Cissé (born in 1969) and Aliou Diack (born in 1987) have all emerged from this formal and academic education to embody, each in his own time, the revival of an African aesthetic that today transcends the borders of Senegal and presents to the world a globalised African art scene with deep roots in their country of origin.

Heir to the intellectual movements that shook Africa in the second half of the 20th century, Senegal, through Senghor's cultural policy and the emergence of dissident currents of thought from the mid-1970s onwards, is one of the rare Black African countries whose art history has been written and is still the subject of much research to this day. Curated by visual artist Jeewi Lee and Océane Harati, this exhibition is a pretext for exploring the artistic history of this West African country, between the filiation and dissidence of its tutelary figures and the artistic currents that have left their mark on African aesthetics beyond the borders of Senegal.

From the beginning of the 20th century (4), a number of pan-African congresses were organised by black intellectuals from Africa and its diasporas to give substance to the political demands that would lead, from the end of the 1950s, to the gradual decolonisation of the African continent by Western colonial powers (5). This long march towards independence was fuelled by the theories of intellectuals and activists who expressed their ideas through periodicals such as La Revue du Monde Noir, Légitime Défense, L'Étudiant noir and Tropiques, published by Aimé Césaire in the early 1940s. One of the most active, and now a famous publishing house, is Présence Africaine. Founded in 1947 with the support of international intellectuals, researchers and writers by Alioune Diop (6), a philosophy professor born in Senegal, the magazine soon became a mouthpiece for all the aspirations and actions undertaken to ‘define African originality and hasten its integration into the modern world ’(7).

In 1959, issue 59 of this magazine published the recommendations made at the Second Congress of Black Writers and Artists (8) in favor of a large-scale cultural event celebrating the creativity and diversity of the arts in Africa and its diasporas (9). The foundations of the Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres were laid. It would be held seven years later in Dakar, Senegal.

Supported by the great figures of negritude, Alioune Diop and Aimé Césaire, President Léopold Sédar Senghor announced the broad outlines of the event in a paper he presented in Rome in 1959. In it, he presented the ‘constructive elements of a civilisation inspired by Black Africa’ and emphasised the functional nature of the work of art, made ‘by all and for all’ and therefore socially engaged. After defining stylistic notions such as rhythm and the analogical image to demonstrate that African art is part of a ‘mystical-magical world’, Senghor concludes by emphasizing the need to develop a new humanism, in which liberated peoples would be committed to building a Black-African civilisation; self aware of its identity, and not content to import ‘the political and social institutions of Europe, and as well as the cultural institutions’ (Senghor 1959) (10) .

Following on from this speech, Senghor, who had just been elected President of the Republic of Senegal after its independence, became the champion of negritude and the initiator of a global contemporary art movement in Senegal (11). As early as 1960, he set up a number of institutions to support the cultural policy and diplomacy intended by the new head of state in the wake of independence. These included the Ecole des Arts (Public Art School), which soon grouped together several entities, including the Ecole Normale Supérieure d'Education Artistique (ENSEA), the Ecole Nationale des Beaux-arts (ENBA), the Conservatoire National de Musique de Danse et d'Art Dramatique (CNMDAD) and the Institut de Coupe, Couture et de Mode (ICCM). A few years later, in 1966, on the occasion of the first Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres, Senghor inaugurated the Musée Dynamique de Dakar, which hosted the event, as well as the Manufacture Nationale de Tapisserie de Thiès (Manufactures Sénégalaises des Arts Décoratifs de Thiès - MSAD), a key element of his policy of state support for artistic creation.

Driven by the desire to create a new art form, Senghor called on artists from a variety of backgrounds to run L’Ecole des Arts. Major artists of the 60s, such as Papa Ibra Tall and Iba N'diaye, were all involved. In 1961, he invited the Frenchman Pierre Lods, who had just arrived from the Congo where he had been running a painting workshop since 1951 in Poto-Poto, a district of Brazzaville to become a professor of art at the school. Lods embraced a practice rooted in total freedom of expression, in contrast to the highly academic style of Iba N’Diaye whose ‘Atelier de recherches plastiques’ was deeply rooted in a more conventional, western educational practice.

One of Lods' pupils, Théodore Diouf, who trained at the Centre d'Enseignement des Techniques Artisanales in Dakar and then at the Ecole Nationale des Arts de Dakar, found inspiration in this mode of expression that perfectly matched the artistic ideology defended by Senghor. Gradually, the young artist ‘invented a vibrant world of poetry inspired by nature, from which he detached himself through a formal vocabulary resolutely turned towards modernism, thus avoiding an ’assignation to nature, of the representation of an African Eden considered primitive by the critics of the time. In the first decades of Senegal's independence, Théodore Diouf felt the need to theorise his practice; to consider and define his oeuvre. It was a question of decentering, on every level, a world and an international art scene organised by the West, around the West. From the outset, his reflections were at the heart of the burning debates around the creation of a contemporary artistic style that was ‘authentically’ African, which for some was a pipe dream ’ (12).

Present at the Salons des Artistes Sénégalais between 1972 and 1974, he also took part in the major exhibition ‘Art Sénégalais d'aujourd'hui’ held in Paris at the Grand Palais in 1974 and became, in accordance with Senghor's wishes, one of the artistic ambassadors of post-colonial Senegal and its artistic ‘school’, theorised by art historians as the Ecole de Dakar, a label with shifting contours that has been constantly challenged, consolidated and questioned, and whose history continues to be written today (13).

But already in the 1970s, dissident voices were being raised to question the Senghorian legacy, in particular the aesthetic and nationalist aspects of the modernism he promoted. It is in this context that we need to understand the emergence of a collective such as Agit'Art (14), whose criticism of Senghor remained respectful and admirative. The same goes for the Village des Arts, initiated by the artist El Hadji Sy in 1977. Dakar's artistic life was gradually taking shape outside of state structures, invading the city and feeding off its energy (15).

The new president Abdou Diouf (16) created his new programme, ‘Sursaut national’ (17), encouraging the emergence of innovative forms of expression. Under pressure from civil society and artists associated with the Association Nationale des Artistes Plasticiens du Sénégal (ANAPS), the new regime abolished old cultural institutions and events, replacing them with the Galerie Nationale d'Art Contemporain in 1983 and the Biennale Internationale des Lettres et des Arts de Dakar in 1990 (18). During this time Diouf’s regime also removed funding for the cultural activities initiated by its predecessor, abolishing the Musée Dynamique in 1988 , and razing the historic Village des Arts, the current version of which it rebuilt in 1998.

This artistic effervescence, combined with a new economic policy, profoundly transformed the capital of Dakar. Marked by an unprecedented rural exodus, the city adopted new configurations that were all subjects of study for artists who gradually transformed their way of working. Viyé Diba was one of them.

Viyé Diba’s commitment to building infrastructure for Dakar is illustrated by his role as president of the Association Nationale des Artistes Plasticiens du Sénégal (ANAPS) between 1988 and 2000 and by his role as an advisory member of the Biennale d'Art de Dakar, of which he was one of the founders. His work emanates from the city as much as it is inspired by it. Trained at the Institut National des Arts from 1973 to 1977, Diba went on to study at the École Normale Supérieure d'Education Artistique from 1980 to 1983 before moving to France in 1985, where he completed doctoral studies in urban geography at the University of Nice, focusing his research on urban public space. Marked by the demographic changes in the city of Dakar from the 1980s onwards, Diba turned it into his field of visual experimentation. Through the collection, he ‘moved away from the conventional use of paint, canvas, and frame to make art, choosing instead to explore materials associated with daily life in Dakar. These materials included roughly hewn wooden planks, cotton cloth, and a variety of salvaged objects which he incorporated into increasingly well-structured yet abstract compositions.

By the mid 1990s, Diba’s mixed media compositions with heavily modified and augmented surfaces gained interest from the international art world and made a name for him as one of Dakar’s -- and Africa’s -- most esteemed artists.

His commitment to advancing knowledge about Dakar’s art and artists is exemplified by his many invitations to residencies and his participation in public conversations. Diba’s disposition to collaboration is part of his legacy which continues to take form in a new space, called Manifa, which he founded in 2022 to host artists’ residencies and exhibitions in Dakar’ (19).

The institutional and political history that was written between 1980 and 2000 is essential to understand the artistic landscape in which the third generation of Senegalese artists will appear, following those of the leaders of independence movements and those of the Dakar School. Soly Cissé and Aliou Diack, heirs to forty years of art history rich in innovation and theoretical thought, embody the essence of this period. Both artists were trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Dakar, and thus benefited from an incredibly rich artistic education combined with a global perspective.

In an interview with French journalist Roxana Azimi in 2016, Soly Cissé states: ‘I'm a product of the Dakar School of Fine Arts, which teaches you to be conventional, not to break out of the academic mold. I was afraid to cross the line. I had to unlearn, get rid of the constraints and impose myself’ (20). Nourished by the major figures of the Western art scene at the beginning of the 20th century, Cissé constructs his own mythology, a guide through which we can understand his work. He does not restrict himself to two-dimensional works like Diba before him, Cissé nevertheless continues to use canvas and paper in his painting and drawing, playing with formats. Collage-assemblage techniques, sculpture and installations are also an integral part of his visual vocabulary, which he uses liberally to his heart's content to address current events. Ecological, economic and cultural issues are at the heart of his creations, as is the social realm, addressing universal struggles in the face of obscurantism.

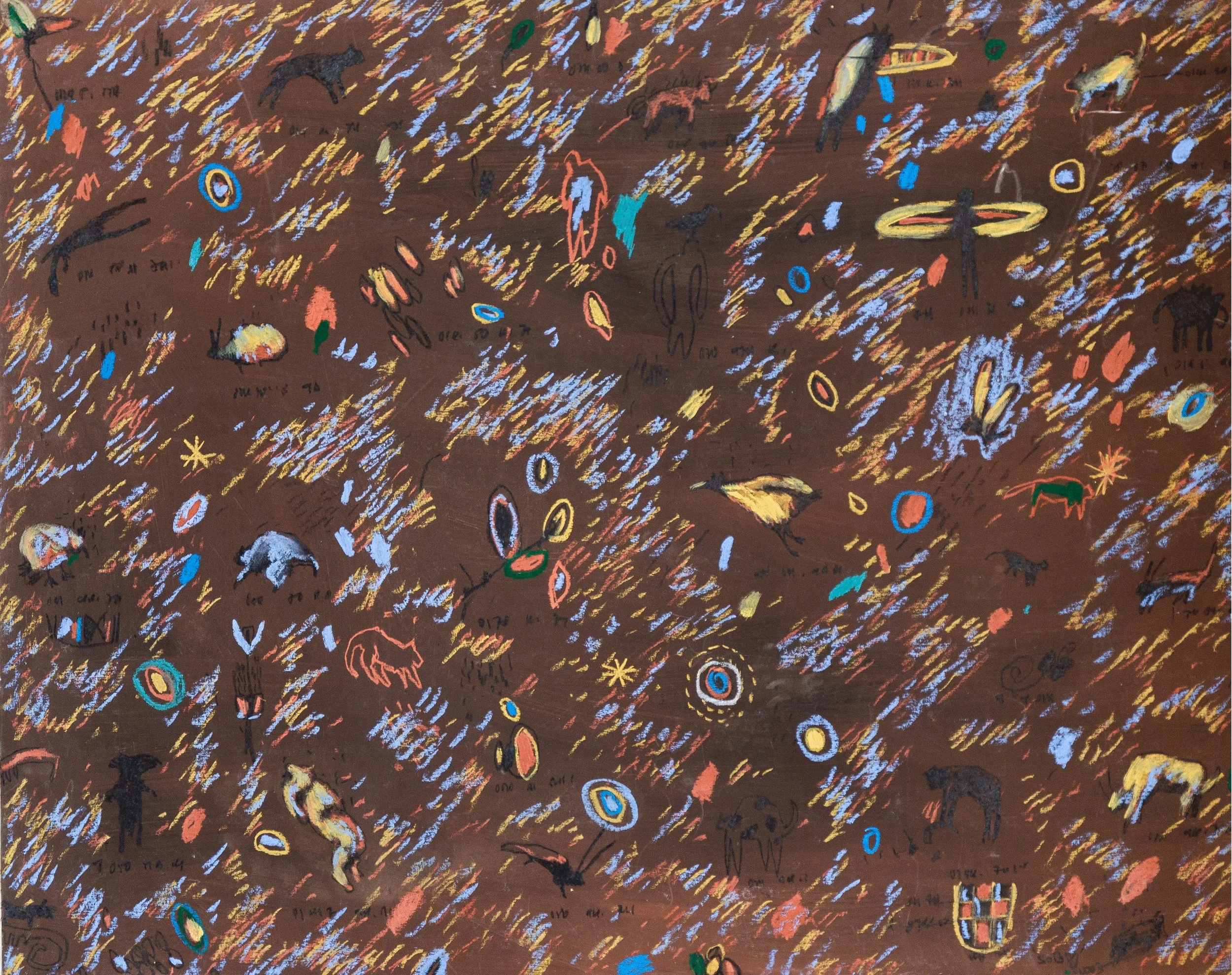

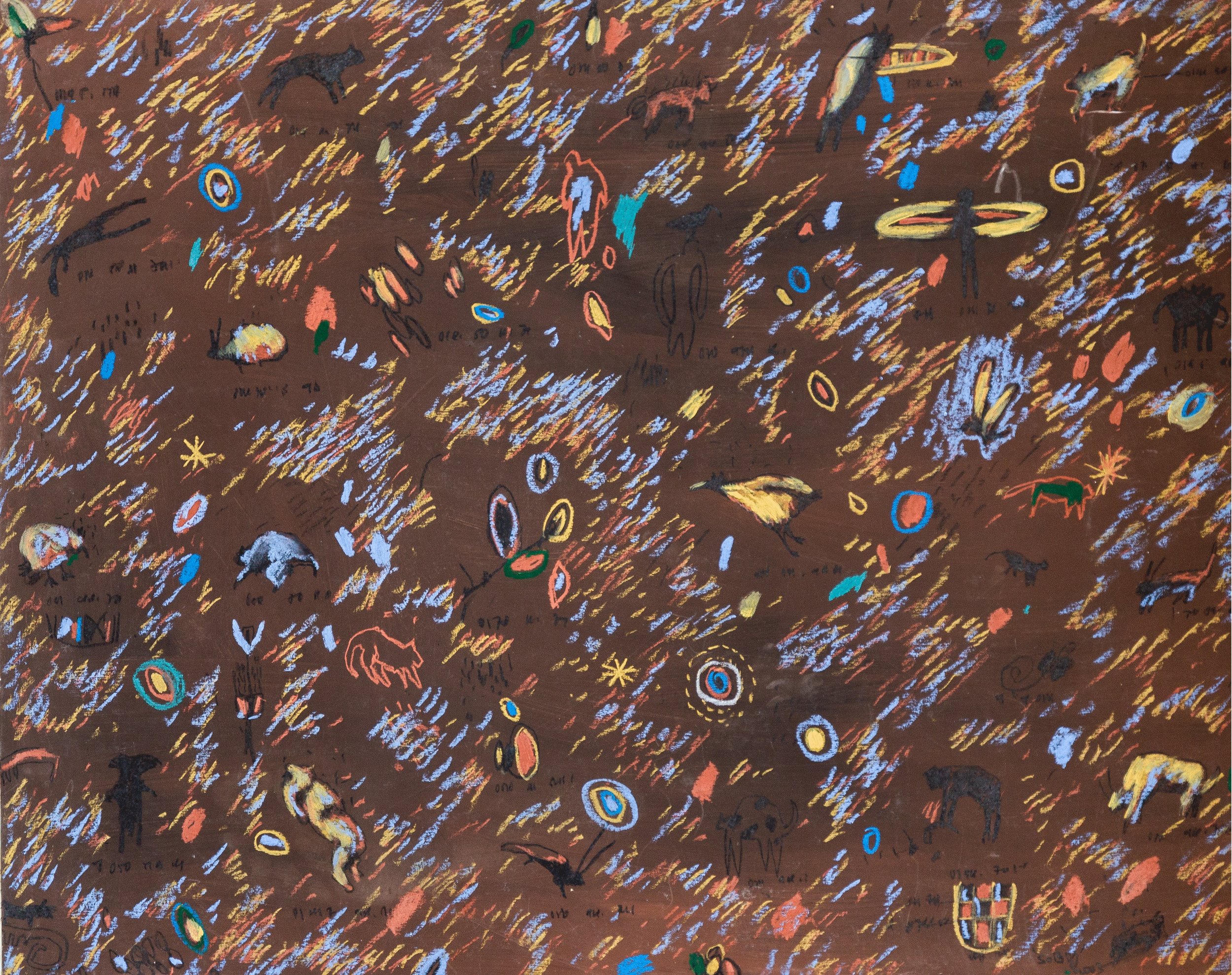

Aliou Diack applies the methods theorised by Joe Ouakam just as much as the extreme freedom or silent pedagogy (21) developed by Pierre Lods. Marked by his childhood spent in the forests on the outskirts of Dakar, the artist's canvases evoke the omnipresent nature of his youth. Using a technique akin to performance art, Diack (Re)activates his senses, sharpened by hours spent in nature, within the pictorial space. ‘I paint as a farmer works, sowing his seeds and ploughing the land’. Diack places the canvas outside, on the ground, sprinkles it with pigments and waits to see what happens. As the winds and rains blow, random shapes emerge, as if drawn by nature, and the painter then intervenes, often with charcoal, to support one or other of the suggested forms. Sometimes he even walks on the canvas, just as he used to walk through the forest. ‘The canvas is abused so that it can marry with the earth. I want the pigments and shapes to absorb the canvas, for it to disappear.” (22)

In 2023, Océane Harati brought together the artists Théodore Diouf and Viyé Diba for a discussion tracing the Senghor years and his influence on the development of Senegalese art. On this occasion, Viyé Diba acknowledged, in retrospect, his affiliation with the Dakar School, recognising himself as a ‘distant child of Senghor’. In this discussion between the two artists, the legacy of the former president seems to transcend the quarrels of the 70s and 80s to converge in a single movement of the third generation of artists from the Ecole de Dakar, nurtured by international art movements of our times. It is embodied here by the artists Soly Cissé and Aliou Diack.

While Senghor's legacy is indisputable in the definition of a Senegalese national art, it is important to note that the protest movements and the Dakar Biennale of Contemporary Art, one of the oldest and most important on the continent, have helped to shape the Senegalese art scene by placing it on the world stage. Senghor's visionary spirit and successive cultural policies have helped to make Dakar the dynamic hub it is today, attracting numerous researchers, art historians and experts of all kinds in search of ‘relics’ of this ‘almost’ forgotten modernity. While the youngest artists, such as Soly Cissé and Aliou Diack, have been exhibiting at international biennials and contemporary art fairs for the past decade or so, it is worth noting that there has recently been a revival of interest in the continent's modern artists, creating a link between the pre-colonial period and independence.

Following in the footsteps of researchers, an art market dedicated to Africa's modern and contemporary art scenes is taking shape. Fuelled by private collectors, galleries, fairs, auction houses and museums, it is gradually helping to establish the history of art on the African continent, which has been left in the shadows for too long.

Charlotte Lidon

August 2024

NOTES

Niam n'goura ou les raisons d'être de Présence Africaine is the title of the inaugural article in the “Présence Africaine” magazine, written by its founder and editor Alioune Diop. In a footnote, the Toucouleur proverb is translated as follows: Niam n'goura vana niam m 'paya, toucouleur proverb: “Eat to live”, not ‘eat to get fat’.

President Senghor officially announced the festival to the Senegalese nation in a radio broadcast on on February 4, 1963.

Léopold Sédar Senghor was the first President of the Republic of Senegal from 1960 to 1980..

1919 saw the creation of the 1st Pan-African Congress, calling for the decolonization of Africa and the West Indies, with its main demands being an end to racial discrimination, respect for human rights and equal economic opportunities. Since 1919, eight congresses have been held. The most recent was held in Accra, Ghana, in 2015.

Ghana became the 1st country to gain independence in 1957, followed by Guinea in 1958. Senegal gained independence on April 4, 1960.

Among the intellectuals supporting the magazine were Aimé Césaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Jean-Paul Sartre, Théodore Monod, James Baldwin, Joséphine Baker and Picasso.

Quote from Alioune Diop on the occasion of the publication of the magazine's 1st issue.

The first Congress of Black Writers and Artists was held in Paris in 1956 on the initiative of Alioune Diop and the magazine Présence africaine, which he had founded in 1947. A second and final congress was held in Rome from March 26 to April 1, 1959. In 2006, UNESCO organized events commemorating the 50th anniversary of the first congress in the same Sorbonne amphitheatre.

E. Ficquet, L. Gallimardet, Enjeux du colloque et de l'exposition du Premier Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres à Dakar en 1966, “Présence Africaine”, n°10, 2009, p. 134-155.

Ibid.

On Senghor's cultural policy, see the catalog of the exhibition held at the musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac, Senghor et les arts - Réinventer l'universel, Paris, 2023.

C. Desportes, Théodore Diouf, cinquante ans de création, OH Gallery, 2023. For a more in-depth study of the artist's work, please consult the complete exhibition text available from the gallery.

Ibid.

The Agit'Art collective was founded in 1974 on the initiative of three Senegalese intellectual and artistic figures: artist and poet Issa Samb (1945 - 2017, known as Joe Ouakam), painter El Hadji Sy (b. 1954) and filmmaker Djibril Diop Mambéty (1945-1998).

J. Grabski, Conceptualizing Art World City: The Creative Economy of Artists and Urban Life in Dakar in Déborder la négritude, Arts, politique et société à Dakar, Les Presse du Réel, 2020, pp.147-164.

Abdou Diouf was President of the Republic of Senegal from 1981 to 2000.

On the “national revival”, see M.C. Diop and M. Diouf, Le Sénégal sous Abdou Diouf. État et société, Paris, Karthala, 1990.

E.H.M. Ndiaye, Dakar-Vortex: pour des géographies quantiques de l’art in Déborder la négritude. Arts, politique et société à Dakar, Dijon, Les Presse du Réel, 2020, p. 133.

Ibid.,

R. Azimi, Soly Cissé: “ma peinture est une lutte”, Le Monde, 11 Avril 2016.

Terminology used by Viyé Diba during a discussion with Théodore Diouf in April 2023 initiated by OH Gallery.

E. Outtier, Aliou Diack, peintre chamane, Diptyk, n°67, Spring 2024, p.86.

évènements

events

T A L K

Wednesday, September 18th, 2024

18h-22h

Localisation

Video recording available at a later date.

GÉOLOCALISATION

LOCALISATION

Œuvres

WORKS

A PROPOS

JEEWI LEE

Jeewi Lee (b.1987, Seoul) is a Berlin based visual artist whose multidisciplinary practice (site-specific installations and interventions, video, image series) examines memory, time and decay.

Lee studied painting at the Berlin University of the Arts and at Hunter College University in New York. She graduated in 2014 as a master student in Fine Arts at the University of the Arts Berlin and hold her MFA in Art in Context. Her work has been shown internationally in many different exhibitions and Lee works on many artistic projects between Berlin, Seoul and Dakar.

She is one of the team-member of the Salon am Moritzplatz and part of the project-collective Dry Ocean, which consists of artists based in Berlin and Dakar.

OCÉANE HARATI

CHARLOTTE LIDON

Trained in art history at the École du Louvre, Charlotte Lidon worked at the Musée des Arts d'Afrique et d'Océanie de la Porte Dorée, then at the Institut du monde arabe, before specializing in the art market, first in galleries, then at the international auction house Sotheby's, which she joined in 2011 in the Classical Arts of Africa and Oceania department.

Keen to promote modern and contemporary African art at auction, she played an active role in the creation of the Modern & Contemporary African Art department in 2016, creating and participating in sales held in London. In Paris, she organizes various events, discussions, meetings and visits to exhibitions and artists' studios within the auction house.

In 2021, Charlotte Lidon took over as head of the department dedicated to modern and contemporary African art within the Parisian auction house PIASA.

An art historian sworn in by the Compagnie Nationale des Experts en Art, Charlotte Lidon now pursues her activities as an independent. Brokerage, expertise, consultancy, research and writing on the arts of the African continent are at the heart of her practice, and contribute to the visibility of the continent's artists and artistic players on the international scene.

Copyright Alain Polo