Sambou Diouf, par Dulcie Abrahams Altass

RETOUR

Sambou Diouf, by Dulcie Abrahams Altass for OH GALLERY

As I write, the sounds of Eid morning carry through my window. Just yesterday, my street was home to flocks of sheep and rams who served as playmates for the neighbourhood’s children, the beasts always pristine thanks to the daily baths that saw them lathered up and rinsed down by their proud owners. Neighbours, having now returned from the mosque, are participating in one of the holiest activities of the Muslim calendar and the Senegalese year. The words of artist Sambou Diouf come to mind, that in the ritual sacrifice of the ram one witnesses a particular mise en scène, a liturgical staging that for the artist demonstrates the fusional relationship between human and animal that is a driving energy in Senegalese society.[1] Rituals such as this one, replete with their signifiers and symbols and that so powerfully animate life and art here, find themselves at the heart of Diouf’s pertinent and necessary practice.

C1932, 2019, technique mixte sur toile, 230 x 215 cm

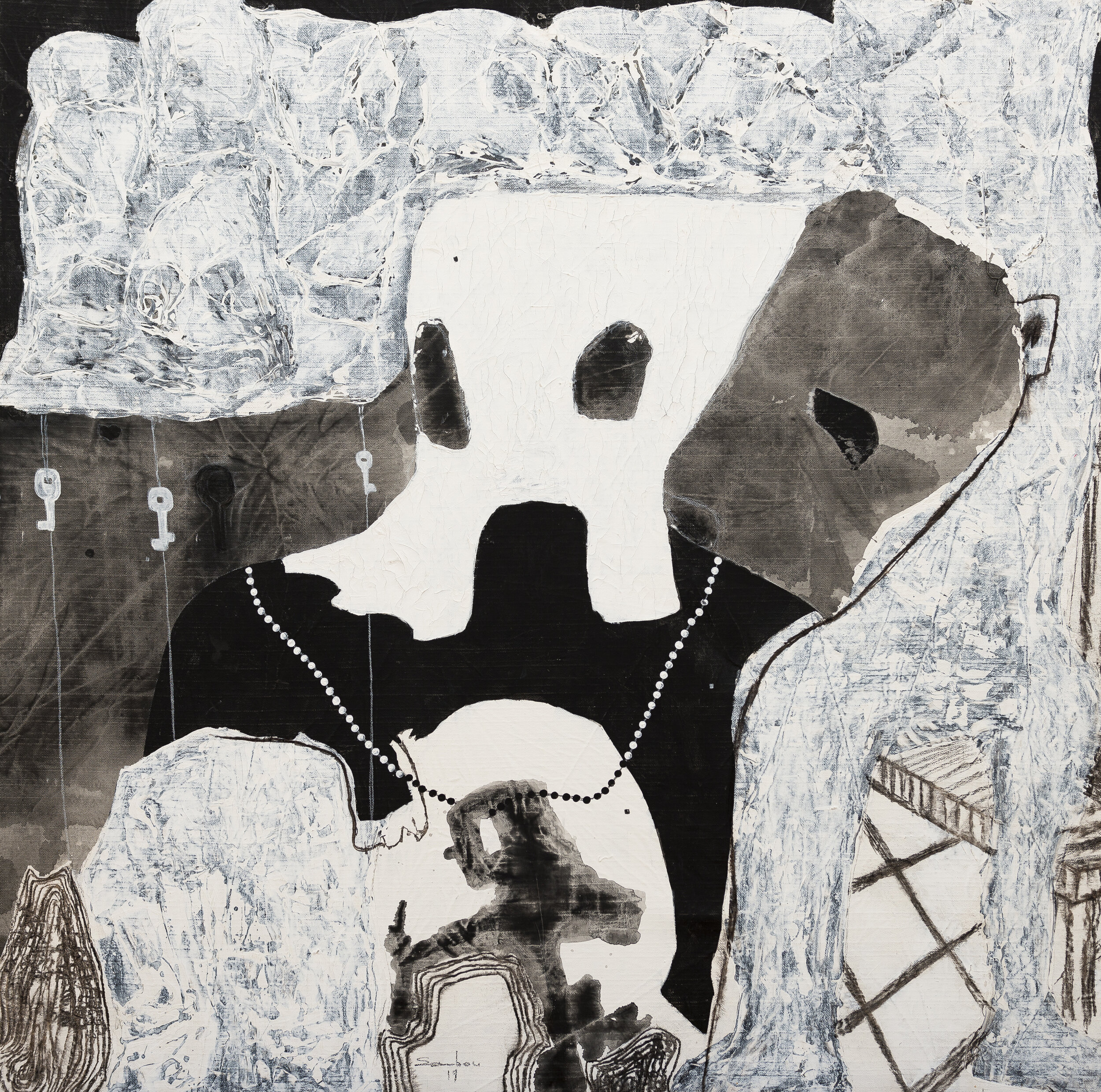

Sambou Diouf is an artist who embraces the creative context from which he has grown, using his paintings to enter into dialogue with his predecessors and peers. As such, his interest in the symbiosis between human and animal in Senegal is shared with a number of other artists of his generation, among them Aliou Diack - also known as Badou - and Serigne Ibrahima Dieye. In the early 2000s, doyen Iba Ndiaye developed a series of paintings born from his own interest in the Eid ritual, Tabaski, and Diouf’s mentor Soly Cissé is also renowned for his troubling scenes of interspecies metamorphose and interaction that emerged around the same period.[2] The 2019 exhibition Les Fabulistes featured works by Diack and Dieye, bringing them together around the proposition that a young generation of artists were drawing on the fable and its form to explore contemporary Senegalese society.[3] In a number of Diouf’s paintings dating predominantly from 2018 such as C1932 and C303, shapes of animals recur, foregrounded in the pictorial space but rendered in smudges that evoke a presence which is constant but not dominant, much like in society in general. And indeed, Diouf traces his entry into a life of art making to a fortuitous meeting wherein the animal played a key role.

C0029, 2018, technique mixte sur toile, 192 x 155 cm

The young Diouf had known an Ivorian in the Patte d’Oie neighbourhood of Dakar who sold cow horns, apparently attempting to adorn them with decorations that were in the eyes of the artist of an insufficient quality. So Diouf showed his own renderings of scenes from the famous Leuk le Lievre fables to the salesman, and the two thus began working together.[4] We see clearly that from his earliest encounters with artistic production, Diouf was engaging with not only the animal as allegory but as actor in ritual too. C0029, a painting from 2018, is clearly host to an animal form in the centre of a universe full of depth and layers, inhabited by ambiguous figures and hatching and lines that evoke barriers. This painting, like many of his other pieces, thrills in the way that it signals another series in an inter-work dialogue that is one of the hallmarks of Diouf’s practice.

Art historian Alex Potts claims that a work of art “...points to or evokes a significance quite other than what it literally is as object through conventions of which we may or may not be consciously aware”.[5] Sambou Diouf’s paintings are particularly fascinating in this regard, as not only do they call upon and complicate numerous signs that carry great significance for Senegalese society, such as the Eid ram, but these signs also journey back and forth through his different series. We might consider the hooded, or masked, figures, or the coffin shape, or the ubiquitous key that features heavily in Portraits but also in earlier and later works. What’s more, Diouf pays homage to his predecessors by not only signalling aspects of their work but in taking up their mantle and creating spaces to explore these aspects further. Referring to the well known Ecole de Dakar movement that flourished and then fell in tandem with the political career of Senegal’s first post-independence president - Léopold Sédar Senghor - Diouf strives in part to pick up where they left off and to lean into the evolution he feels they were never able to have.[6] He is notably reverent when it comes to the late sculptor Moustapha Dimé, and although their mediums differ, Diouf’s homage is exquisite; Dimé was known for giving second lives to objects abandoned or forgotten but familiar to Senegalese viewers, and Diouf goes one step further by giving second lives to the practices of the artists he respects, recovering that which he feels has been erased.[7]

One of the most recurrent aspects of Sambou Diouf’s intertextuality are the masked or hooded figures already mentioned above. They are widely present in his works from 2018 and 2019, more often than not in pairs or larger groups, suggestive of humans but without any recognisable features that would allow us to distinguish them as individuals. Instead, faces are replaced by a black and white shroud of texture and shadow, and we must thus return to Alex Potts and ask how they may function to signify meaning, as signs. Unique features have throughout history been replaced with traits that are in a given shared cultural context representative of particular qualities, what Roland Barthes would describe as “connoted meaning”.[8] It is thus worth pausing on what kind of connotations the figures might call upon in contemporary Senegal, with one extremely ubiquitous image coming to mind. Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba is the historic founder of the Mouride brotherhood, a widely followed branch of Sufi Islam in Senegal and beyond, and his image is omnipresent in the country, finding its way onto t-shirts, hologram stickers adorning taxis and graffiti across Dakar. And yet, the sole photo of Bamba that exists and that serves as the basis for these millions of replica images, shows very little of the figure’s physical traits. Rather, we see him swathed in white cloth, with only his eyes somewhat visible. For anyone familiar with Senegalese visual culture it is hard not to see echos of Bamba’s turbaned face in the characters that people Diouf’s paintings.

Cérémonie, 2019, technique mixte sur toile, 140 x 140 cm

Dernier jour, 2019, technique mixte sur toile, 140 x 140 cm

Curiously, the figure has become central in an entire body of work by the artist that, in a tantalising twist, came together in a recent exhibition named Portrait. In over a dozen paintings, viewers are faced with the figure depicted predominantly from the torso upwards, each time wearing the key seen in earlier pieces on a long beaded pendant that seems to reference the prayer beads used in both Catholic and Muslim traditions and widely available in Senegal. These portraits are distinguishable from one another by the colours used in Diouf’s thick impasto style and through subtle differences in stance, but they are nonetheless a study in seriality. And is it not through seriality, through its repetition, that a sign’s meaning becomes embedded in a collective psyche? Indeed - remaining attentive to the symbolic space of contemporary Senegal - scholars Allen Roberts and Mary Nooter Roberts argue that the aura of Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba’s image derives from its ubiquity, not least because the negative of the original photograph is seemingly lost.[9] When viewing these paintings, named Portraits but revealing no individual traits and instead visually suggesting the icon of Mouridism, this series thus prompts one to ask what the artist might be pointing to with regards to notions of individual and collective identity in contemporary Senegal. As viewers we are denied the possibility of engaging with individuals, and are invited to look deep into folds and shadows that hint at nothing other than what we might visually associate with their forms, notably the image of Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba.

The key does however unlock a door that leads to a different type of portrait. During the period in which Sambou Diouf was working on the portraits, there is a piece that stands out as signalling an event whose memory is far from ubiquitous, that the viewer accesses as if peering through a large keyhole. The massacre of Chasselay took place in the Rhône region of France between the 19th and 20th June 1940, and saw scores of West African soldiers who had been fighting to defend the Allied territories executed in cold blood by German troops. Known as Senegalese Riflemen, their French counterparts had been spared by the German forces in an act of outright racism, and they are today buried at Chasselay in a Senegalese tata, where the French earth has been mixed with soil transported from Dakar. This extremely painful episode is little known, although the recent discovery of a series of photographs showing the riflemen in the minutes leading to their death has brought its horror into sharp relief. In a total reversal of the modalities of the photograph of Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba, the riflemen’s faces are visible, but their identities are unknown.

In 2019, Diouf produced Tirailleur (“Rifleman”), a powerful painting that takes the tropes of Portraits but transforms them for this homage. The work is itself shaped like a coffin, one of Diouf’s recurring motifs expanded and becoming the container for the portrait itself, a gesture of care towards the riflemen who were only given proper burials some two years after their execution. The portrait of the anonymous rifleman reaches its limits at the edges of the keyhole within which it is framed, that sits inside the coffin form. These cues remind the viewers that we are privy to something we would not normally, or should not, see. In the context of France’s frequent refusal to acknowledge vast and significant aspects of its colonial and racist past, Diouf allows us to peek through the keyhole of history’s closed door. This sense is reinforced when confronting the face of the rifleman, partly shrouded, partly visible, a glimmer of yellow light evokes an eye, a concentrated darkness a mouth open in shock or fear. Diouf’s figure has features, and is wearing the traditional red jacket of the rifleman’s uniform that one sees today before the gates of Senegal’s presidential palace, and yet we are nonetheless denied knowledge of who he may be, of his name or his age or who he loved or what he hoped for. This denial calls up the conditions of the riflemen’s entry into both World Wars, and the cold anonymity of their deaths. Tirailleur is a piece that, like its subject matter, deserves to be studied and experienced by a large public. Its display is imperative.

Zeumb, 2019, technique mixte sur toile, 190 x 135 cm

Sambou Diouf’s key takes us a step further, to a meeting with the figure of Zeumb (2019), for the moment the only painting of its kind by Diouf to be exhibited. Zeumb bears in many ways a likeness to the portraits, enough in any case for the viewer to glean some sort of relationship between the two; it depicts a figure from the torso upwards, its body rendered much like those of the Portraits series, and we once again are met with the key. In Zeumb’s world though, the key is large and sat atop the figure’s head, a head with a face and eyes and a nose and mouth and teeth that we are privy to, and our protagonist is steady against a smooth camomile yellow background that bears none of the agitation and mystery of the scratched and wrinkled backgrounds from Portraits, nor the horror and sorrow of the Tirailleur. While we know little of who Zeumb may be, after the endless teasing of the other anonymous paintings there is an easy and light intimacy with the figure here. Is Zeumb the counterpart of the rifleman? Is Zeumb proof of survival, of a life force and of individual identity who emerges as a figure of hope against the backdrop developed by Diouf? He can certainly be read that way, his vital presence a celebration of black male identity at a time when it remains shunned, oppressed and threatened.

Sambou Diouf is an artist heavily invested in the symbolism and visuality of the society in which he operates as well as the artistic traditions that came before him, whose paintings become terrains of possibility where these signs and traditions can be worked through. This is not a given in a society that operates under significant pressure from socially conservative factions, and one must ask what it means for Sambou Diouf to take the literal and metaphorical mask off his figures, and to begin revealing Zeumb to his viewers. What is certain is that Zeumb announces a new phase in the artist’s work, one that - if we know how to find the right keys - will surely show itself to be as rich, and relevant, as those that came before.

[1] Author’s own interview with the artist, July 2020

[2] B. M. Diop “Le thème du sacrifice du mouton chez l’artiste peintre Iba Ndiaye (1928-2008)” in Éthiopiques numéro 83

[3] Exhibition Les Fabulistes, Galerie Le Manège, Dakar, 2019, Aliou Diack et Serigne Ibrahima Dieye

[4] Author’s own interview with the artist, July 2020

[5] A. Potts “Sign” in Critical Terms for Art History, ed. R. S. Nelson and R. Shiff, The University of Chicago Press, Second Edition, 2003, p.20

[6] Author’s own interview with the artist, July 2020

[7] Idem

[8] R. Barthes Image, Music, Text, trans. S. Heath, Fontana Press, 1977, p.17

[9] “A Saint in the City: Sufi Arts of Urban Senegal” Allen F. Roberts and Mary Nooter Roberts in African Arts, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Winter, 2002), p.62

ABOUT DULCIE ABRAHAMS ALTASS

Dulcie Abrahams Altass is a British curator and art historian who lives in Dakar, Senegal. She is Curator of Programs at RAW Material Company in Dakar where she has co-curated numerous exhibitions including Toutes les fautes qu’il y avait dans le monde, je les ai ramassées (2018) and PO4 (Blackout) (2019). Recent discursive projects of note with RAW Material Company include Kan jaa ta; From the shadow into the light (Bamako Encounters Photography Biennale, 2019) and Condition Report 4: Stepping out of line; Art collectives and translocal parallelism (Dhaka Art Summit, 2020). Her work in Senegal has included research on diverse topics ranging from the country’s performance art history to the nexus of hip hop and contemporary art in the country, and her writing has been published in SUNU Journal, Making & Breaking, ESPERANTO and Obieg. Dulcie has been a member of artist’s collective Les Petites Pierres and is a co-founder of the social justice group Show Up Dakar.

Dulcie Abrahams Altass est une commissaire d’exposition et historienne de l’art britannique qui habite à Dakar, Sénégal. Elle est Commissaire des programmes à RAW Material Company où elle a été co-commissaire des plusieurs expositions dont Toutes les fautes qu’il y avait dans le monde, je les ai ramassées (2018) et PO4 (Blackout) (2019). Parmi ses projets récents avec RAW Material Company comptent Kan jaa ta; From the shadow into the light (Rencontres de Bamako, 2019) et État des Lieux 4: Sortir du rang ; Collectifs artistiques et parallélisme translocal (Dhaka Art Summit, 2020). Son travail au Sénégal comprend de la recherche sur des sujets aussi divers que l’histoire de l’art-performance sénégalais et les interrelations entre le hip-hop et l’art contemporain à Dakar, et ses textes ont été publiés dans SUNU Journal, Making & Breaking, ESPERANTO et Obieg. Dulcie a été membre du collectif d’artistes Les Petites Pierres, et elle est cofondatrice du groupe de justice sociale Show Up Dakar